Photos from Croatia

| Home | About | Guestbook | Contact |

CROATIA - 1965-2018

A short history of Croatia

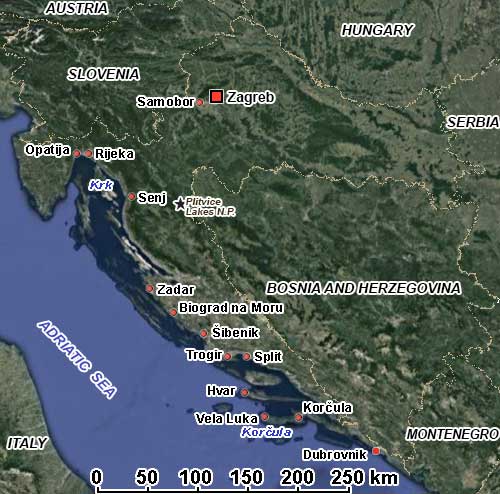

The Republic of Croatia is a country in southeastern Europe of almost 22,000 km² and a population of nearly 3.9 million. Almost 92% define themselves as Croats, and around 3% as Serbs. The country consists of three historical regions: Croatia proper, in the centre, with its capital Zagreb, Slavonia to the east, and Dalmatia along the Adriatic coast. It shares borders with its former fellow Yugoslav republics of Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, and Hungary to its northeast. The area of present Croatia has been inhabited since prehistory. Fossils of Neanderthals and many remnants of prehistoric cultures have been found. Later, Illyrians and Liburnians settled here, and Greeks established colonies on some islands. The Roman Empire ruled here from 9 CE; Emperor Diocletian was born in this region, and his large palace in the coastal city of Split is still there and part of the historic core of the city.

It is not entirely sure where the present Slavic Croats came from; the most likely theory is that they migrated from present-day southern Russia and Ukraine or southern Poland when migrations took place between the 7th and 9th century CE. A Kingdom of Croatia in the year 925, when Tomislav, known as Duke of Croatia, was crowned its first king. The kingdom reached its peak in the 11th century, until the year 1102 when it entered into a personal union with Hungary: for the following four centuries, it was ruled by a parliament (Sabor) and a ruler (called a Ban) who the King of Hungary appointed. In the 15th century, Croatia was threatened by the Ottoman Turks while the Venetians controlled most of Dalmatia, except the city-state of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), which had become an independent republic. In 1526 King Lajos (Louis) II of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia (present-day Czechia) was killed in the Battle of Mohács, which led to the annexation of large parts of Hungary by the Ottomans. The following year the Croatian Parliament chose Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg, ruling Austria, as its new ruler; the condition was the protection of Croatia against the Ottoman Empire and respecting its political rights.

Western Bosnia, originally part of Croatia, stayed under Ottoman rule and never came back under Croatian control; the border is still there. Slavonia, the area in the northeast, was regained in 1698 after the 15-year-long Great Turkish War; the Ottomans were defeated. The Kingdom of Slavonia was established in 1699; in 1745, it was administratively included in both Kingdoms of Croatia and Hungary. Between 1797 and 1809, the French under Napoleon gradually occupied the Adriatic coast and parts of inland Dalmatia, ending the independence of the Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik). But these “Illyrian Provinces”, as they were called, were occupied by the Austrian Empire in 1813. It led to the formation of the Kingdom of Dalmatia, with its capital in Zadar. The coastal region further north, including Senj, was restored to the Kingdom of Croatia, except the city of Fiume (now Rijeka), a semi-autonomous “Corpus separatum” (separated body), since 1779 directly subject to the Hungarian Crown.

A Croatian National Revival, part of the “Illyrian Movement”, a pan-south Slavic cultural and political campaign, started around 1835 by young Croatian intellectuals. They advocated establishing a standard language as opposed to Hungarian; in the Hungarian Revolution, Croatia, under Ban (viceroy) Josip Jelačić, chose the side of Austria and helped defeat the Hungarians in 1849. In 1867 the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy, a personal union between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, was established. A year later, Austria reached a settlement with Hungary in which the Kingdom of Slavonia and the Kingdom of Croatia, separate Habsburg Crown Lands, were united into the single Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. Although under the suzerainty of the (Hungarian) Crown of Saint Stephen, it maintained a significant level of self-rule. But the Kingdom of Dalmatia remained under de facto Austrian control. In 1878 Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina following the Treaty of Berlin. The sectors that had been military frontier regions, borderlands established against incursions from the Ottoman Empire, were restored to Slavonia and Croatia in 1881.

In 1906 Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary and a group of scholars conceived a proposal to federalise the dual monarchy. But in 1914, he was assassinated in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, triggering the outbreak of the First World War and the dissolution of the dual monarchy. On 29 October 1918, the Croatian Parliament (Sabor) declared independence and joined the other Slavs in the southernmost parts of Austria–Hungary. They proclaimed the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, saying their ultimate intention was to unite with Serbia and Montenegro in a large South Slav state, which happened 33 days later: on 1 December 1918, the state joined the Kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, with Petar I, the king of Serbia, becoming its first monarch. However, Italy had annexed the Dalmatian port city of Zadar (Zara) and some islands. The city of Rijeka, which had been separated, was disputed between Italy and the new Slav kingdom. But on 12 November 1920, they signed a treaty acknowledging the independent Free State of Fiume; this lasted until 22 February 1922, when Italy annexed the city while the kingdom absorbed the area to its south.

In 1921, upon the death of Petar I, he was succeeded by his son Alexander I. That same year a new constitution was adopted, in which the country became a unitary state: the Croatian Parliament was abolished, and the Croatian autonomy ended. This act caused tensions, culminating in 1928 in the murder of Stjepan Radić, the Croat Peasant Party leader who had pressed for federalism. King Alexander I abolished the constitution on January 1929 and introduced a personal dictatorship. To unite the various ethnicities into a more significant national identity, he also officially changed the name of the country to the “Kingdom of Yugoslavia”, a name that had already unofficially been used and simply meant “South-Slavia”, or “country of the South Slavs”. He rearranged internal borders, not corresponding to historical regions, to weaken regional loyalties, but this only caused resentment. Alexander was assassinated in Marseille, France, during an official visit in 1934. In Croatia, more voices wanted either federalism or outright independence. On 7 January 1929, a Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organisation, formally known as Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionary Movement, was founded by Ante Pavelić and three others. Pavelić had very early objected to Yugoslavia having a Serbian king and spoke in favour of Croat independence. They advocated an “ethnically pure” “Greater Croatia”, covering the entire historical and ethnic area of the Croats. It became a terrorist organisation, planting bombs on trains bound for Yugoslavia, murdering Serbian Orthodox priests and burning their churches; three Ustaša members were implicated in the murder of King Alexander. The Ustaše was banned (Ante Pavelić was arrested in Italy but released in 1936), but in the late 1930s, they managed to infiltrate the Croat Peasant Party and other organisations.

On 6 April 1941, the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia despite the pact a few days earlier it had signed with Nazi Germany. Four days later, Slavko Kvaternik, one of the founders of the Ustaše, proclaimed the formation of the “Independent State of Croatia” (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH) in Zagreb, declaring Croat independence. Ante Pavelić and other Ustaše members returned from Italy to Zagreb, where on 16 April 1941, Pavelić announced a government and himself the title “Poglavnik”, Chief, equivalent to the German “Führer”. It constituted what is now the Republic of Croatia (without Istria), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Syrmia (now part of Serbia) and the Bay of Kotor (in Montenegro). However, a few days later they were forced to cede parts of Dalmatia with its islands and Kotor to Italy. Germany and Italy divided the “independent” state into two spheres of influence; when Italy capitulated in 1943, the NDH annexed that area again. Ustaše units carried out bestial atrocities against the Serbian Orthodox population. The regime had declared in May 1941 that one-third of Serbs had to be killed, one-third expelled, and one-third forcibly converted to Catholicism. Entire families, including the aged, women and children, were slaughtered. They cooperated with the Nazi occupiers, murdering Jews and Gypsies as well. They had concentration camps, the largest of which was Jasenovac. But also, at the same time, the Yugoslav Royalist and Serbian nationalist Četniks pursued a genocidal campaign against Croats and Muslims.

King Petar II and the government fled Yugoslavia in April 1941. On 22 June 1941, a resistance movement, the First Sisak Partisan Detachment, was formed in central Croatia; this was the spark that began the Yugoslav Partisan movement, a communist, multi-ethnic anti-fascist resistance group led by Josip Broz, commonly known as “Tito”. Croats were the second-largest contributors, after Serbs, but the first in per capita terms. In 1943 they were recognised by the Allies. Tito established the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) in November 1942. The movement grew fast, and with Allied support and the assistance of Soviet troops, the Partisans gained control; in 1945, the Partisans, numbering over 800,000 strong, defeated the Armed Forces of the Independent State of Croatia and the Wehrmacht. Many tried to flee to Austria, and Ante Pavelić fled to Italy, disguised as a priest, but later managed to get to Argentina, where he was shot by a Serb in 1957. He survived and eventually received asylum in Spain, where he died in 1959. In 1943 The AVNOJ convened in Jajce, Bosnia and committed to remaking Yugoslavia into a democratic federation of six republics, with Josip Broz Tito as president. On 9 May 1944, the Federal State of Croatia was officially founded, one of the constituent members of what was called Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. After the war, on 29 November 1945, it became the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia and the People’s Republic of Croatia one of its six members. Croatia was the last of the republics to adopt its constitution on 18 January 1947. Like the other republics, it forbade them from seeking independence. On 7 April 1963, Yugoslavia was renamed “Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia”, and Croatia officially became the Socialist Republic of Croatia. Although a series of reforms had taken place, there were increasing efforts by the constituent republics to protect their economic interests. Between 1967 and 1971, the “Croatian Spring” was a political conflict in which the rising prominence of Croatian nationalism became more apparent.

On 4 May 1980, Tito died, and a collective leadership from the different republics took over, but tensions became more pronounced; Croatia and Slovenia both wanted more local autonomy, while Serbs supported a more centralised state. In 1990 the first multi-party elections took place in Croatia. Franjo Tuđman’s win caused further tensions, with Serbs even declaring a separate “Republic of Serbian Krajina” in the eastern regions of Croatia, a move that was not recognised. Croatia held a referendum on independence on 19 May 1991, which was overwhelmingly approved - although most Serbs boycotted it. On 25 June, Croatia declared independence and the dissolution of its association with Yugoslavia. In August, conflict with the Yugoslav People’s Army (dominated by Serbs) and various Serb paramilitary groups had escalated to a full-blown war. By late 1991 one-third of Croatia was under the control of Yugoslav troops and Serb militias, who killed thousands of civilians in a fierce campaign of terror, expelling Croats and other non-Serbs from their homes. In retribution, Serbs living in Slavonia and Krajina also were expelled or had to flee. The war effectively ended in August 1995 with a decisive victory by Croatia. The 200,000 Serbs in that self-proclaimed “Republic of Serbian Krajina” fled, and Croat refugees resettled the area from Bosnia and Herzegovina after the war there.

The Republic of Croatia was recognised on 15 January 1992 by the European Economic Community and the United Nations. Its first president was Franjo Tuđman, head of government until he died in 1999. Since its independence, Croatia has undergone a process of democratisation and economic reform; it became a member of NATO in 2009 and a member of the European Union in 2013. On 1 January 2023, Croatia officially became a Eurozone member and entered the Schengen Area, allowing travel without a passport and border controls. Despite the challenges it faced in the past, Croatia has managed to establish itself as a stable and prosperous country with a vibrant tourist industry. Croatia has beautiful natural landscapes, a long and complex history, and a rich cultural heritage. The country has been shaped by its location at the crossroads of Central Europe, the Mediterranean and the Balkans. Its unique mix of influences, from the Roman Empire to the Venetian Republic and the Ottoman Empire, has given Croatia a distinctive culture and identity. Today, Croatia is a modern, democratic country that is proud of its past and is looking forward to a bright future as a member of the European Union.